M is for Madraseh (school), 2023

Artspace Mackay, Queensland

Finalist in the 2023 Walyalup Fremantle Print Award

Artist book documentation by Catherine Black - Exhibition photography by Artspace Mackay

Catalogue essay by Louise R Mayhew

A is for Alphabet

Deanna Hitti’s M is for Madraseh (School) unfurls the alphabet across the gallery’s walls, recalling young children’s textbooks. You might know the type, reading: a is for apple, b is for bear, c is for cat . . .

B is for Book

Despite the work’s childhood origins, Hitti reveals the extraordinary complexity of language and learning, using a juvenescent text as an entry point to larger conversations on family, culture, history and power. Creating a sensorially and conceptually delightful tension between simplicity and intricacy, her installation of 26 letters transforms childhood memories of introduction to the written word into larger, intersecting and unruly discourses. The following essay charts a few.

C is for Childhood

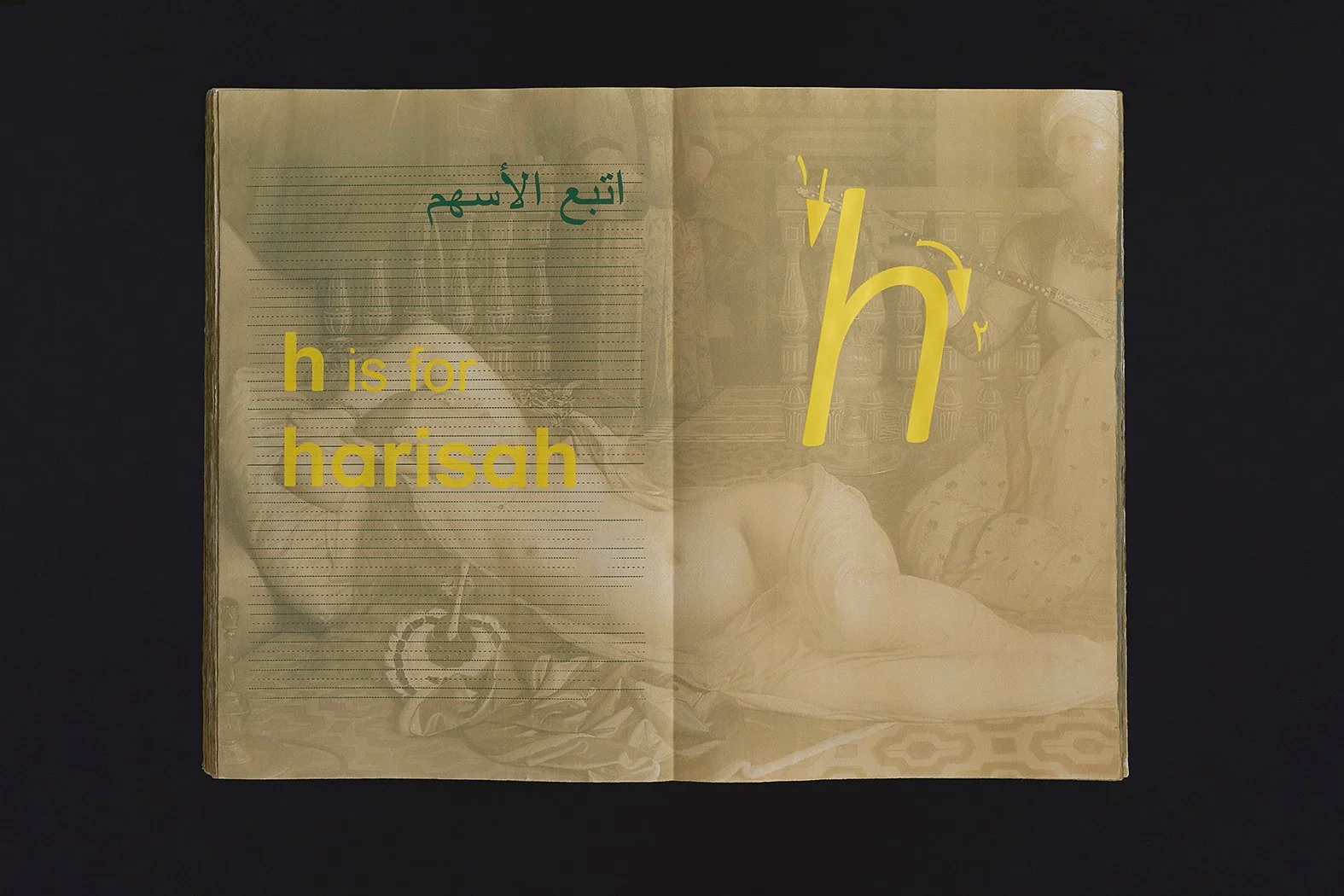

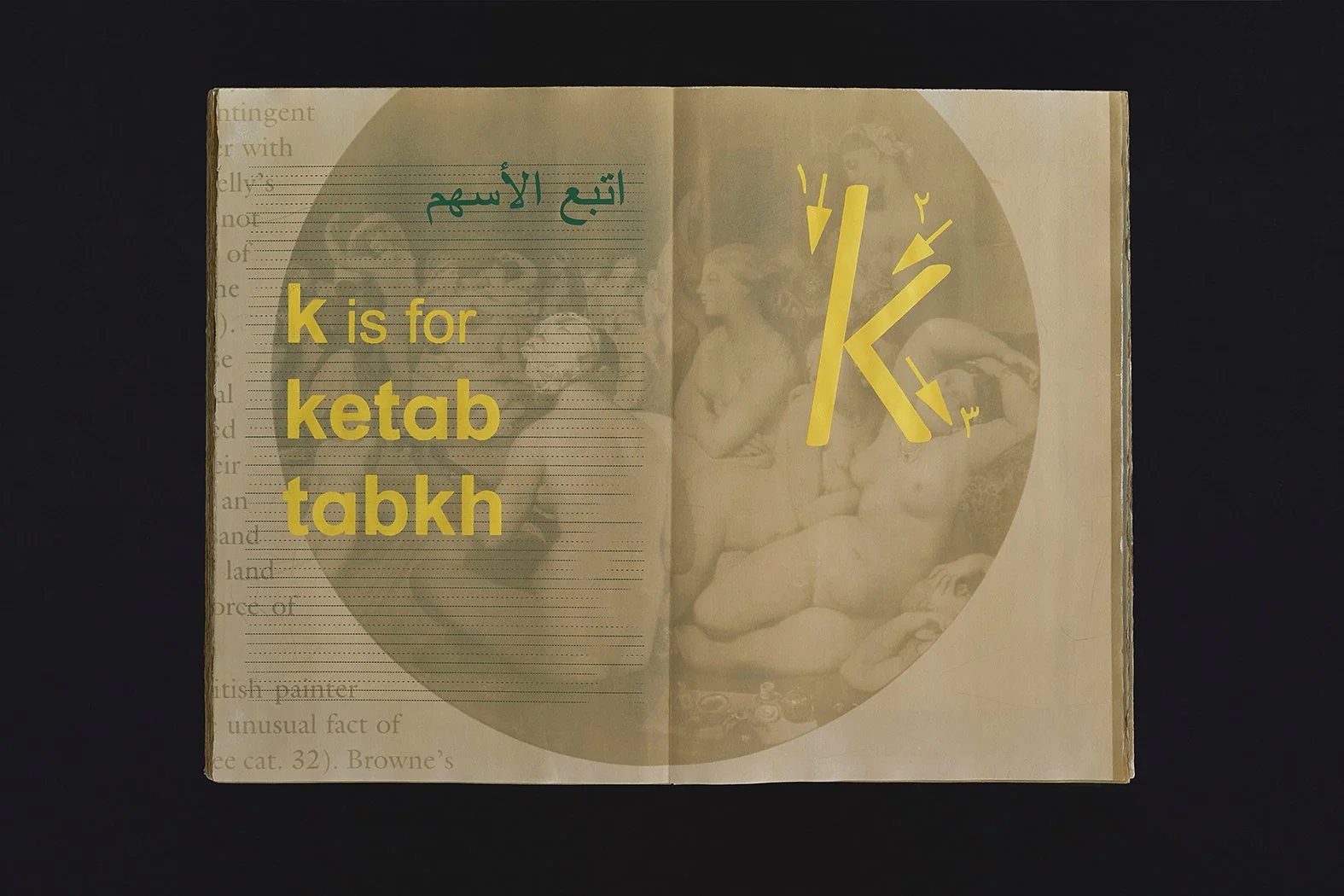

Each of Hitti’s prints presents a single archetypal letter—a, b, c, etc.—in the hyper-neat and legible font of the keyboard, very much unlike the scrawled, uneven text of children learning to hold a pencil. Borrowing from her childhood reader—which she still owns—she combines each letter with diagrammatic arrows and written instructions for practising the letter’s strokes. Though not all of us can read these instructions.

D is for Discourse

For a linguist, Hitti’s work confirms the opening principles of semiotics. Here language is a complex system of signs and meanings that belie immediate knowing or comprehension. We are not born reading. Nevertheless, language can be learnt, through practice and immersion.

E is for English

When we’re children, this truth is abundantly clear. Writing appears foreign, cursive is just as indecipherable as Egyptian hieroglyphics, and the world is full of words and symbols not yet known. Yet as we grow, words become familiar. We learn, sometimes with difficulty and sometimes with surprising ease, to read and write. Some of us learn multiple languages or different codes, adopting Australian Sign Language, mastering musical notation, or practising morse code, with a shared purpose, always, of communication.

F is for Family

Through Hitti’s use of the Arabic abjad (script), non-Arabic speaking audiences are reunited with the experience of language as a code, of reading as possible for others yet impossible for themselves.

Both of the artist’s parents are from Lebanon. The two emigrated separately to Australia when they were young. In turn, Hitti’s first language is Arabic. She learnt English—including how to write English—with the guidance of her Arabic-English reader. This explains Hitti’s use of Arabic to describe the Latin-script alphabet of Modern English and her titular madraseh, or school, as both the place (noun) and action (verb) of her childhood home.

G is for Gold

Colour also communicates meaning in Hitti’s work. Her golden letters speak of the morally-divisive luxury of gold. Throughout art history, gold has stood in for the expanse of Heaven in Byzantine mosaics and symbolised the decadence of Islamic Kingdoms in Orientalist paintings.

H is for Hegemony

This binary split in potential meanings (Biblical gold as morally-divine, Islamic gold as morally-corrupt) expands Hitti’s work from a nostalgic reflection on childhood to larger, historical and politicised meditations on hegemonic discourse, namely and especially the West’s representation of the East.

I is for Ingres

Imagine porcelain-skinned women laid out, nude, upon their beds and at their bath. Rich textures, tapestries, architectural interiors and landscapes suggest non-specific and timeless locales, somewhere in the Near East. Behind them, dark-skinned women fill subservient roles. In related paintings, men clash, ride horses, sell slaves and camels, or gather in public space, languid, to listen to the sounds of busking minstrels.

J is for Jewellery

Hitti excerpts and reproduces details from such paintings in M is for Madreseh. As your eyes drift across their surfaces, what stories do they tell through jewellery, clothing, and design? Notice the gleam of pearls, the intricacies of furniture and convincing rendering of clothing. Richness, sensuality and difference abound.

K is for Knowledge

Despite never travelling to such locations, leading Orientalist Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres painted these scenes for the Paris Salon. Alongside the equally-French Eugène Delacroix and Jean-Léon Gérôme, Ingres drew on larger narratives and power dynamics to imagine the French-colony of Lebanon, as well as Turkey, Greece, North Africa and additional Near Eastern countries, as unfamiliar, extravagant and corrupt.

L is for Loss

In the opening sentences of Orientalism: Western Conceptions of the Orient (1978), Edward W. Said describes Lebanon in the French imaginary.

On a visit to Beirut during the terrible civil war of 1975–1976 a French journalist wrote regretfully of the gutted downtown area that ‘it had once seemed to belong to . . . the Orient of [18th- and 19th-century French Romantic writers] Chateaubriand and Nerval.’ He was right about the place, of course, especially so far as a European was concerned. The Orient was almost a European invention, and had been since antiquity a place of romance, exotic beings, haunting memories and landscapes, remarkable experiences. Now it was disappearing; in a sense it had happened, its time was over. Perhaps it seemed irrelevant that Orientals themselves had something at stake in the process, that even in the time of Chateaubriand and Nerval Orientals had lived there, and that now it was they who were suffering; the main thing for a European visitor was a European representation of the Orient and its contemporary fate, both of which had a communal significance for the journalist and his French readers.”[1]

M is for Myth

As Said carefully details throughout the remainder of his text, Oriental Lebanon as constructed and imagined by the West, was a myth. In his words, Orientalism was: “A mode of defining the presumed cultural inferiority of the Islamic Orient . . . [and] part of the vast control mechanism of colonialism, designed to justify and perpetuate European dominance.” The counterpart to Ingres’ and the Orientalists visual construction of the Near East was their construction of France. By contrast, Parisian society was pictured as familiar, cultured, rational, and genteel.

N is for Narrative

Hitti counters Orientalism’s myths with her artwork-as-archive. She replaces the discourse-from-a-distance of colonising French (as well as other European and American) Orientalists with her embodied knowledge of growing up Lebanese-Australian, of playing tawla with her Father, of drinking nabidh with her family, of mourning the loss of her native tongue. In shuffling the alphabet, she also prioritises the meaning-making methods of rearrangeable collections over the linearity of grand narratives and their defined beginnings and ends.

O is for (Dis)Order

Following her lead, this essay similarly loosens its grip on order.

PQR is for Print, Quotation, Reproduction

By using the print-based methods of screen-printing and cyanotypes, Hitti points to and complicates the authority of the written word and the printed page. In her quotations and reproductions, she mirrors Post-Structuralist philosophies, which complicated semiotics’ structural logic by turning attention away from the author and the text to the reader and the intertextual spaces in between.

S is for Silence

. . .

T is for Truth

“Art is even closer to the truth. It is truth.”—Anselm Kiefer.[2]

U is for Unconscious and Unknown

Within each of her prints, Hitti further reiterates language and communication is always, like her excerpted details, partial and incomplete; always, like her drawing together of text from her childhood reader and imagery from 19th-century paintings, in conversation, collaged and layered with other meanings and possibilities.

Declaring the death of the author, Post-Structuralist Roland Barthes explains:

Any text is a new tissue of past citations. Bits of code, formulae, rhythmic models, fragments of social languages, etc., pass into the text and are redistributed within it, for there is always language before and around the text. Intertextuality, the condition of any text whatsoever, cannot, of course, be reduced to a problem of sources or influences; the intertext is a general field of anonymous formulae whose origin can scarcely ever be located; of unconscious or automatic quotations, given without quotation marks.[3]

VWX is for Vignette, Writing, eXpansion

Beyond the heavy philosophies of Cultural Marxism, the complex theories of Structuralism, and the pervasive histories of Orientalism, Barthes turns us to Hitti’s other uncited pasts, to the realms of photography and architecture, domestic objects and the decorative arts, installation and artists books captured within her vignettes and conjured by her Arabic text. Such references shift for every viewer, who bring their own memories, feelings, knowledge and experiences to the white cube of contemporary art.

Y is for You

Hitti tailored this work to the gallery’s architecture, spending time with the contours and lighting of the space to envisage how you entered the room, to imagine where you might sit, and to recreate your point of view. In thinking of you, she hopes to recreate the intimate experience of reading a book, thinking of her art as a one-on-one conversation between you and her. In this rearrangement between author, text and reader, I wonder what you think and feel and see.

Z is for 100 new beginnings

In the artist’s own words: “It’s nice when people take their own stories away.”[4]

[1] Edward W. Said, Orientalism: Western Conceptions of the Orient [1978] (Penguin Group, London, 1995) 1.

[2] Anselm Kiefer, “Anselm Kiefer in conversation,” interview by Elena Cué, Alejandra de Argos, 23 September 2019, https://www.alejandradeargos.com/index.php/en/all-articles/21-guests-with-art/41746-interview-with-anselm-kiefer.

[3] Roland Barthes, Image - Music - Text, ed. and trans. by Stephen Heath (New York: Hill and Wang, 1977) 39.

[4] Deanna Hitti, in conversation with the author, 13 January 2023.